14 August 2014. Biomedical engineers and systems biologists developed an online system that tests the fidelity of engineered cells and tissue to the real-life properties of the cells they aim to emulate. The system, known as CellNet, is the creation of researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston University, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, and described in pair of articles appearing in this week’s issue of the journal Cell (paid subscription required).

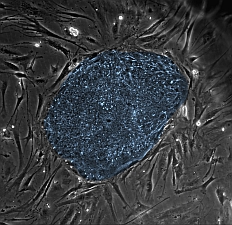

CellNet tests the quality in induced pluripotent stem cells, those reprogrammed from skin or blood cells, as well as specialized cells, — e.g., liver, heart, or brain cells — derived from induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cells, and specialized cells made from other specialized cells. In addition, CellNet highlights improvements in the engineering process to improve cell quality.

CellNet takes a cell’s gene expression profile and returns its likelihood of being classified into one of 16 human or 20 mouse cell and tissue types, which applies strict criteria to determine how close the engineered cells or tissues resemble the real thing, what CellNet calls “training data.” In this process, an algorithm compares the network of genes activated or inhibited in the engineered cell, known as the gene regulatory network, and returns specific improvements for improving the cell or tissue engineering process.

In one study, the team used CellNet to analyze gene expression data from 56 published studies for assessing the quality of 8 kinds of engineered cells created in those studies. In the second study, researchers tested with CellNet two specialized types of direct cell conversions: (1) skin to liver cells, and (2) immune system B cell lymphocytes to macrophages, white blood cells in the immune system that ingest foreign material. In both articles, the researchers found shortcomings in the conversions and highlighted fixes in the genetic engineering process to plug the gaps.

The team likewise identified a few patterns in the conversions for further gene or tissue engineering initiatives. The gene regulatory networks of engineered cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells, for example, were very similar to the networks of cells from embryonic stem cells, suggesting induced pluripotent stem cells can provide a feedstock of about equal quality as embryonic stem cells.

In addition, the gene regulatory network of engineered cells grafted into lab mice begins to resemble the network of the target tissue, suggesting the body is sending signals to the engineered cells to enhance their performance. However, most specialized cells made from other specialized cells retain some of the properties of the original cells, which depending on their purpose, can be an advantage or disadvantage.

The team still notes, however, that transforming induced pluripotent stem cells into specific tissues remains a more effective strategy than converting one specialized cell into another, despite the laborious process of first creating pluripotent stem cells. With pluripotent stem cells, the engineered cells or tissue have gene regulatory networks more like the real-life cells or tissue.

“Most attempts to directly convert one specialized cell type to another have depended on a trial and error approach, says Patrick Cahan of Boston Children’s Hospital and the principle designer of CellNet in a Wyss Institute statement. “Until now, quality control metrics for engineered cells have not gotten to the core defining features of a cell type.”

CellNet is freely available online, and can be used as a hosted service or downloaded to run locally.

Read more:

- Trial Testing Amniotic, Umbilical Grafts to Heal Wounds

- Early Trial Shows Neural Regrowth Effects on Depression

- Pfizer, Biotech to Partner on Brown Fat Cell Research

- Heart Disease in Lab Recreated with Stem Cells, Chip Device

- Engineered Cardiac Tissue Helps Veins Return Blood to Heart

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.