11 May 2017. Biomedical engineers developed and demonstrated in lab animals a closed-loop system that monitors and controls delivery of drugs to meet an individual’s personalized needs. A team from Stanford University and University of California in Santa Barbara published its findings in yesterday’s issue of the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering (paid subscription required).

Researchers led by Stanford engineering and radiology professor Tom Soh are seeking a way to provide precise and personalized drug doses based on an individual’s needs. A person’s genetic and physiological characteristics, as well as chemistry of the drugs being administered, can make it difficult to prescribe correct doses at various times. In addition, external factors, such as other drugs being taken, can affect the way a person interacts with medications, sometimes with dire consequences.

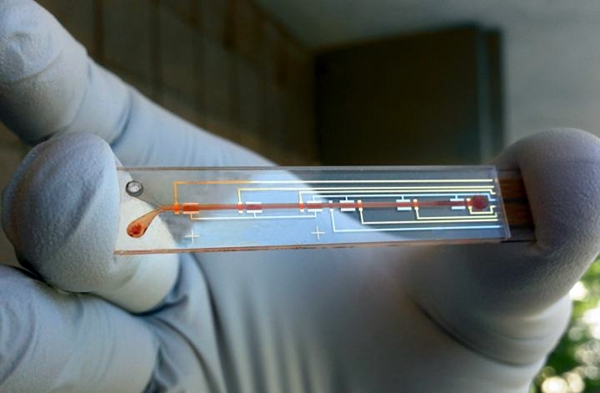

Soh’s lab at Stanford, and earlier at UC-Santa Barbara, studies natural nucleic acid substances called aptamers that recognize and bind strongly to specified targets. In binding to its targets, aptamers conform to the target’s chemistry, thus changing their shape in predictable ways. In the study, Soh and colleagues use this property of aptamers to devise a sensor that monitors the shape of designated aptamers, reporting on changes such as greater or lesser quantities of the targeted drugs.

The researchers’ system uses this biosensor in a monitor, which combined with a controller and infusion pump, dispenses drugs, making adjustments as needed in real time. The monitor’s software keeps track of an individual’s personalized body chemistry, which alerts the controller to change the drug’s concentration as needed. The system is designed as a platform technology for use with a wide range of medications and patient types.

The Stanford-Santa Barbara team tested the closed-loop system with the cancer chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, prescribed for a number of blood-related and solid tumor cancers. In this proof-of-concept study, researchers used their system to administer doses of doxorubicin to lab rats and rabbits, at specified dosages, keeping the doses at those levels in real time. The team reports introducing other compounds known to cause wide swings in doxorubicin levels, with the system able to respond and change the quantities to prevent sharp spikes or dips in the animals’ drug levels.

“This is the first time anyone has been able to continuously control the drug levels in the body in real time,” says Soh in a Stanford University statement. “This is a novel concept with big implications because we believe we can adapt our technology to control the levels of a wide range of drugs.”

The researchers feel a system of this type can be a vital tool for precision medicine, and plan to miniaturize the technology into a self-contained device implanted or worn by patients, such as individuals with type 1 diabetes who need to control levels of both insulin and glucagon to regulate their blood glucose. Pediatric cancer patients, for whom prescribing safe and effective drug doses is difficult, would also be early targets for the technology.

Soh is a scientific adviser to Aptitude Medical Systems, a company in Santa Barbara that licenses his earlier research on aptamers at UC-Santa Barbara. Scott Ferguson, CEO and founder of Aptitude Medical Systems, is a co-author of the paper.

More from Science & Enterprise:

- Sound Waves, Nanotech Delivery Boost Cancer Drug

- Smartphone-Controlled Cells Produce Insulin on Demand

- Artificial Pancreas Shown Feasible for Young Children

- Mobile App-Controlled Patch Reduces Migraine Pain

- Biofeedback Device Reduces Panic Attacks in Trial

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.