Scientists from Germany, France, and the U.S. have developed a new process to regulate dangerous fluctuations in heart rhythms with far less energy and pain than current methods. The team’s findings appear in the current issue of the journal Nature (paid subscription required).

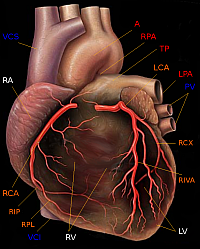

The regular human heartbeat is controlled by the heart’s electrical system. An electrical signal extends from the top of the heart to the bottom, which causes the heart to contract and pump blood. The process repeats with each new heartbeat.

An arrhythmia occurs when the signals get interrupted or out of rhythm, which can cause the heart to beat too fast, too slow, or with an irregular beat. While some arrhythmias are not immediately harmful, others can become more serious, leading to lack of sufficient blood flow to the brain or body.

Up to now the treatment for chronic arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, is a strong electric shock to force the heart signal back into its regular rhythm. However, that shock of up to 4,000 volts can damage tissue surrounding the heart and cause pain to the patient.

The team led by Stefan Luther from the Max Planck Institute and Flavio Fenton from Cornell University have devised a new technique called Low-Energy Anti-fibrillation Pacing (LEAP) that reduces the energy needed for defibrillation by 84 percent as compared to conventional methods.

While the current technology uses one large shock to affect the entire heart, LEAP sends a series of smaller, low-energy pulses to synchronize the heart tissue. In tests with dogs using a cardiac catheter, the researchers created a sequence of five weak electrical signals in the heart. The technique stops the irregular beats for a brief moment, then resumes regular, synchronized heartbeats.

LEAP takes advantage of other normal, functioning components of the heart, such as blood vessels and fatty or fibrotic tissue. The weak signals from LEAP stimulate cells in these parts of the heart that in turn suppress the chaotic signals and regulate the entire organ.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), designed to treat ventricular fibrillation, a life-threatening arrhythmia, could be an early application of LEAP. The new technique could eliminate pain, prolong battery life of the device, and thus reduce the frequency of surgical device exchanges.

Read more: Trial Tests Heart Valve Replacement Without Opening Chest

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.