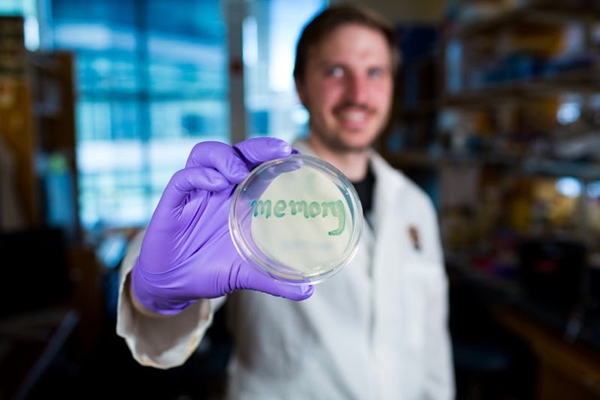

David Riglar hold a petri dish with engineered bacteria that turn blue when exposed to inflammation signals. (Wyss Institute, Harvard University)

30 May 2017. A bioengineering team developed a synthetic form of bacteria that live in the gut, and detect inflammation in lab mice for 6 months. Researchers from the Wyss Institute, a bioengineering research center at Harvard University, and Harvard Medical School, describe their findings in yesterday’s issue of the journal Nature Biotechnology (paid subscription required).

The team led by Wyss Institute biochemistry professor Pamela Silver is seeking non-invasive methods for monitoring intestinal conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, a collection of disorders including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, marked by inflammation in the digestive tract lining. People with inflammatory bowel disease suffer severe diarrhea, pain, fatigue, and weight loss, as well as a risk of life-threatening complications.

Diagnostics and treatments for inflammatory bowel disease can be difficult because of the gut’s inhospitable environment that can cause genetic changes live microbes, and its ability to quickly clear bacteria from the body. To overcome these obstacles, Silver and colleagues needed a solution that provides a stable long-term sensor of gut inflammation in mammals.

The researchers designed the sensor, in this case, to detect and monitor the chemical tetrathionate, produced by gut inflammation that results from Salmonella and other harmful bacterial infections. The team started with a benign form of the Escherichia coli or E. coli bacteria, and adjusted its genetic wiring to respond to the presence of tetrathionate.

The genetic modifications involve interactions of 2 genes in lab mice. The genes are designed to indicate the presence of tetrathionate, where one gene produces a characteristic protein, and blocks the expression of a second gene. When inflammation subsides and tetrathionate disappears, they trigger expression of the second gene producing its own protein, but also blocking the first gene indicating the presence of tetrathionate.

The researchers added a memory function to the genetic wiring as well as a detection mechanism. The memory function, adapted from a virus that attacks bacteria, acts as a toggle with the 2 interacting genes. In the presence of tetrathionate, the first gene becomes active and toggles the memory function to the “on” position. When the toggle is switched on, a separate reporter gene, beta galactosidase, also produces an enzyme that adds a blue color to the otherwise colorless engineered bacteria.

By turning the engineered bacteria blue in the presence of tetrathionate, gut inflammation can be monitored noninvasively by the fecal matter of the mice. The team tested the synthetic bacteria in lab mice induced with infections causing gut inflammation and other mice genetically altered to produce gut inflammation. In both cases, the researchers report the engineered bacteria were able to detect tetrathionate in mice feces for up to 6 months.

The authors conclude that the tests show engineered bacteria offer another technology for monitoring gut health with living diagnostics. “Our approach is to use the bacteria’s sensing ability to monitor the environment in unhealthy tissue or organs,” says postdoctoral researcher and first author David Riglar in a Wyss Institute statement. “By adding gene circuits that retain memory, we envision giving humans probiotics that record disease progression by a simple and non-invasive fecal test.”

More from Science & Enterprise:

- Engineered Bacteria Designed to Detect Gut Inflammation

- Diet Enhancing Gut Microbes Shown to Slow Type 1 Diabetes

- Company Launches to Discover Gut-Brain Therapies

- Therapeutic Food-Triggered Gut Microbes in Development

- Grant Funding Study of Gut Microbe Protection Drug

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.