5 February 2015. A new report from Brookings Institution says the United States is losing ground to overseas competitors in critical advanced industries that hold the key to the country’s long-term economic future. The study by the Washington, D.C. think tank was discussed in a forum today with six CEOs of U.S. companies and the governor of the nearby state of Virginia.

The Brookings team led by Mark Muro, director of its Metropolitan Policy Program, identified 50 industries as advanced industries, defined as those where R&D spending per worker is in the 80 percentile or higher among all industries, and whose share of workers in occupations requiring a high degree of scientific or technical knowledge is above the national average of 21 percent. The 50 industries include 35 from manufacturing, 12 from services, and 3 in energy sector.

Advanced industries include the most disruptive, market-making technologies, such as additive manufacturing, robotics, genomics, advanced materials, big data analytics, and connecting smart devices into the Internet of things. Companies in these industries tend to cluster in large metropolitan areas, with 70 percent of all advanced industry jobs found in the 100 largest metro regions. San Jose, California is the most concentrated hub with 30 percent of its workforce in advanced industries, followed by Seattle (16%), Wichita (15.5%, mainly aircraft), Detroit, (15%, largely automotive), and San Francisco (14%).

Small numbers of people that pack a big economic punch

As of 2013, say the authors, these 50 industries employed 12.3 million people in the U.S., or about 9 percent of all workers. Yet despite its relatively small size, advanced industries produced some $2.7 trillion in value, or about 17 percent of total U.S. gross domestic product. Advanced industries accounted for 80 percent of engineers employed, 90 percent of all private sector R&D spending, and 85 percent of all patents awarded in the U.S. Moreover, economic activity of the 12.3 million workers in advanced industries support another 14.3 million workers in support or supply-chain jobs.

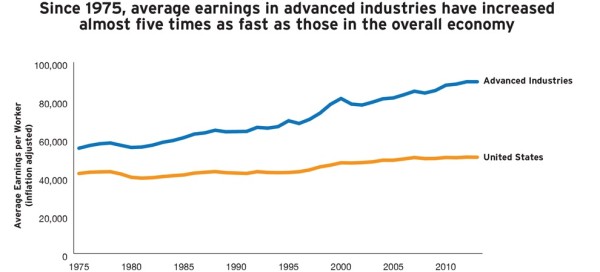

In addition, people working in advanced industries earn better pay, with pay rates rising faster than the rest of the economy. Advanced industry workers earned about $90,000 a year in total compensation in 2013, compared to $46,000 for the average worker in other sectors.Between 1975 and 2013, average earnings of workers in advanced industries grew by 63 percent when adjusted for inflation, compared to 17 percent for other workers.

The higher pay rates extended across education levels, with people earning an average of $53,000 a year as of 2013 in total compensation for some college but no degree, compared to $38,000 a year elsewhere. Workers with an associates degree in advanced industries earned $58,000 a year in 2013, compared to an average of $55,000 a year for a bachelors degree in other industries.

Economic growth in advanced industries largely powered the U.S. recovery, particularly in services, following the Great Recession. Advanced industries overall added 1 million jobs to the U.S. economy since 2010, with employment rising 1.9 times and output gaining 2.3 times more than the rest of the economy. Advanced services, such as architecture-engineering and computer systems design, accounted for 65 percent of the new jobs. Computer systems design alone added 250,000 of those jobs.

Deficits in advanced industry trade

Yet despite the solid and even spectacular performance of advanced industries, their share of the U.S. economy is slipping, while other countries are beginning to pick up the slack. One indicator is balance of trade in advanced industries, where the U.S. ran a $632 billion deficit in 2012, despite exports in advanced industries of $1.1 trillion. The report says the U.S. ran similar annual deficits in advanced industries since 1999.

The trade deficits include areas where the U.S. was once dominant, such as computer and communications equipment, motor vehicles, and pharmaceuticals, as well as computer and information services. On the plus side for U.S. advanced industries are aerospace equipment and intellectual property royalties, with surpluses of $60 billion and $80 billion respectively in 2012.

On another indicator — share of the U.S. workforce in advanced industries — fell 2.2 percent between 2000 and 2010, a larger slippage than in 14 other OECD countries. By 2010, the U.S. ranked 9th of the 14 countries in share of total workforce in advanced industries. In one more indicator of problems ahead, the U.S. has only 4 metro areas in the worldwide leading 50 regions in patent applications: San Diego, San Francisco/San Jose, Boston, and Rochester, New York. Of those areas, only San Diego and San Francisco/San Jose are in the top 20.

Muro and colleagues outlined three sets of recommendations to get advanced industries in the U.S. back on track: a greater commitment to innovation, generate more highly skilled workers to fill good jobs, and rebuild the ecosystems that support advanced industries. Of those recommendations, most of the CEOs discussing the report focused on getting more skilled workers for advanced industry employers.

Filling the skills gap

Eric Spiegel, president and CEO of Siemens Corporation in the U.S., pointed out the disconnect between the skills needed by his company and the few students with those skills turned out by universities. Spiegel described the apprenticeship system in Germany that combines post-secondary education with on-the-job training to produce skilled engineers. He said Siemens began similar apprenticeship programs in Charlotte, North Carolina and elsewhere to build “middle skills” needed to run plants using robots and lasers.

John Lundgren, CEO of of tool maker Stanley Black and Decker, said his company developed training programs with local community colleges to produce the skilled workers needed in his company’s factories. He also cited statistics showing that half of applicants for the 600,000 unfilled factory jobs are disqualified because of criminal records or drug use found in background checks.

The CEOs also supported the recommendation to rebuild the ecosystem supporting advanced industries, as did Governor Terry McAuliffe of Virginia. Katrina Bosley, CEO of Editas Medicine, a start-up developing gene-editing therapies, underscored the importance of basic research funding for the biotechnology industry. Bosley said research into the fundamental nature of genetics led to discoveries of gene-editing mechanisms in bacteria that now make it possible to remove or deactivate mutations causing disease.

Still another need in the support ecosystem is fixing the infrastructure in the U.S. Crumbling roads and bridges were cited by Ron Armstrong, CEO of truck maker Paccar. Likewise, Spiegel said Siemens itself in some cases needed to improve the roads in the vicinity of some plants when local jurisdictions could not do the job in time.

Governor McAuliffe, in a closing discussion with Muro, outlined Virginia’s experience as a location for advanced industries. One resource in Virginia McAuliffe noted for moving ideas from university labs to the marketplace is Commonwealth Center for Advanced Manufacturing or CCAM, a collaboration between 5 universities in Virginia and 21 companies to match university research to business needs. That collaboration, said McAuliffe helps break down barriers and ease companies’ research costs.

The CEOs had no single approach to innovation, where each company used the culture or nature of their industries to take foster new ideas. James Heppelman, president of software developer PTC, said business models in that industry are changing to put more emphasis on service and follow-on sales as much as initial sales, as well as storing data and solutions in the cloud, following Apple’s iTunes model.

Klaus Kleinfeld, chairman and CEO of Alcoa said one his greatest challenges is finding ways to encourage innovative thinking in his company. He told the story of young workers in an Alcoa mill who on their own retrofitted their smartphones with sensors that could monitor the output of aluminum production equipment more closely and less expensively than current technology.

Bosley of Editas Medicine said an advantage to American biotechnology firms was a venture capital community in the U.S. willing to risk billions of dollars on new drug discovery and development. Kleinfeld noted that in addition to more access to venture capital, Americans are more tolerant of failure. “Venture capital seeks out senior management who have failed,” Kleinfeld noted, adding that the experience of failure offers valuable guidance for the next enterprise. Financiers in Europe, on the other hand, avoid managers with a failure in their history.

Read more:

- Patents, Start-Ups Increase in 2013 at U.S. University Labs

- Analysis Uncovers Biotech Commercialization Bottlenecks

- Panel: Federal Science Cuts Hurt U.S. Competitiveness

- Science-Based Enterprises: Great Ideas Beat Venture Capital

- AAAS Pres: Science Drives Innovation, Economic Growth

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.