4 May 2016. Lab tests by a biotechnology company show an engineered protein can block the actions of genes responsible for low normal hemoglobin production in people with inherited blood disorders like sickle cell disease. The findings of researchers from Acetylon Pharmaceuticals Inc. in Boston were reported in April in the journal PLoS One.

Acetylon Pharmaceuticals, a spin-off enterprise from Harvard University and affiliated research institutes, develops treatments for a number of disorders using epigenetic tools that chemically influence expression of genes without changing the underlying genetic sequences. In this study, the Acetylon team led by researcher Jeff Shearstone tested an engineered protein code-named ACY-957, developed to block actions of proteins in the body known as histone deacetylases. ACY-957 is designed to inhibit specific histone deacetylases that prevent production of fetal hemoglobin, which can treat the inherited blood diseases sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia.

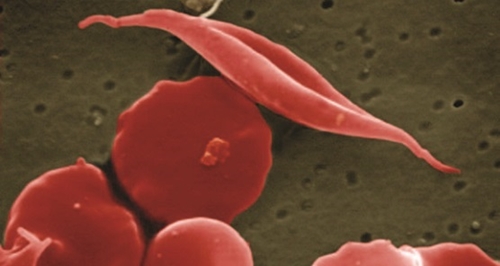

Sickle cell disease is a genetic blood disorder affecting hemoglobin that delivers oxygen to cells in the body. People with sickle cell disease have hemoglobin molecules that cause blood cells to form into an atypical crescent or sickle shape. That abnormal shape causes the blood cells to break down, lose flexibility, and accumulate in tiny capillaries, leading to anemia and periodic painful episodes. Beta thalassemia is a blood disorder that reduces production of hemoglobin, causing pale skin, weakness, fatigue, and more serious complications.

Histone deacetylases interrupt normal expression and transcription of genes by modifying chromatin, the substance in cells with a nucleus that form chromosomes. But these proteins affect a wide range of functions in the body, thus limiting or blocking their actions must focus squarely on precise targets. The authors note clinical evidence that blocking histone deacetylases in general can lead to adverse and toxic reactions.

Shearstone and colleagues assessed ACY-957’s ability to limit two specific types of histone deacetylases or HDACs shown previously to affect production of fetal hemoglobin in red blood progenitor cells that transform into adult red blood cells. The team tested ACY-957 in the lab with blood samples from people with sickle cell disease, and for comparison healthy individuals. The results of gene expression profiles show ACY-957 blocked the actions of the two suspect histone deacetylases, and induced more production of fetal hemoglobin in the red blood progenitor cells.

The Acetylon team also identified mechanisms that brought on these results. The gene profiles showed as well a 3-fold increase in expression of the GATA2 gene that produces a protein binding to other genes that encourage production of blood cells. The increased GATA2 yield, say the authors, results in more intermediate proteins that promote production of fetal hemoglobin.

“These new data will inform the design of future programs at Acetylon,” says Matthew Jarpe vice president of biology in a company statement. Jarpe was senior author of the PLoS One paper.

Read more:

- Patent Granted for RNA Transcription Technology

- Trials to Test New Treatments for Inherited Alzheimer’s

- Study to Test Increasing Ethnic Genetic Disease Diversity

- Gene-Editing Therapy Advances for Rare Immune Disorder

- $45M Raised by Protein Folding Drug Discovery Company

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.