24 May 2019. A neuroscience lab in the U.K. designed a process using virtual reality to detect early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in people with mild cognitive impairment. A team from University of Cambridge and University College London describes the test and its findings in yesterday’s issue of the journal Brain.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition, the most common form of dementia affecting growing numbers of older people worldwide. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says as many as 5 million people in the U.S. were living with Alzheimer’s disease in 2014, with deaths from Alzheimer’s increasing 50 percent from 1999 to 2014. University of Cambridge cites data showing Alzheimer’s disease also affects some 525,000 people in the U.K.

Researchers led by neuroscientists Dennis Chan at Cambridge and Neil Burgess at University College London are seeking more definitive methods for identifying people at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Signs of mild cognitive impairment such as impaired memory are an indicator of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, but loss of some memory may be due to other factors, such as anxiety. This lack of clear-cut indicators of early-stage Alzheimer’s also makes it difficult to enroll participants who can most benefit from clinical trials testing treatments for the disorder.

The team identified a region of the brain called the entorhinal cortex that offers path for better detecting Alzheimer’s disease in its early stages. The entorhinal cortex is part of the medial temporal lobe, a section of the brain that controls memory, and is one of the first areas in the brain damaged by Alzheimer’s. It is also the part of the brain that serves as a mental GPS to recognize spatial positioning and find one’s way through familiar and unfamiliar surroundings. Paper-and-pencil tests of cognitive abilities, say the authors, would not likely catch this functional loss.

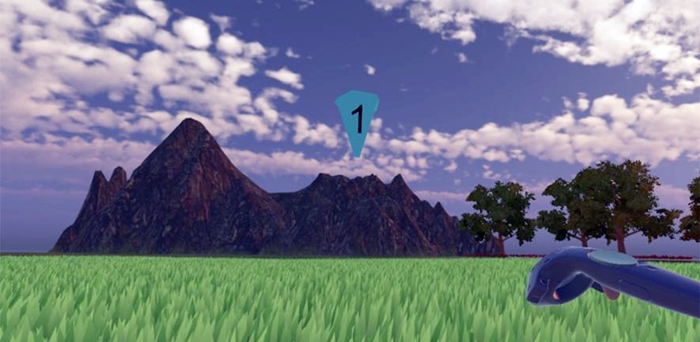

Chan, Burgess, and colleagues hypothesize that people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease would also have difficulty with personal navigation. The researchers developed an virtual reality exercise to simulate a navigation task, and asked 45 individuals at local hospitals and clinics with mild cognitive impairment to take the exercise. The team asked 41 healthy volunteers to take the exercise as well for comparison.

Among 26 of the 45 participants with mild cognitive impairment, the researchers also took samples of their cerebrospinal fluid to test for biomarkers of amyloid-beta or tau proteins indicating the presence of Alzheimer’s disease. And of this group, 12 participants tested positive for these biomarkers and 14 tested negative. The team also asked participants to complete a set of paper-and-pencil cognitive tests used for Alzheimer’s diagnostics and correlated behavioral performance on the navigation test with entorhinal cortex volume using MRI scans.

The results show participants with mild cognitive impairment and testing positive for Alzheimer’s biomarkers recorded more errors on the virtual reality navigation exercise than other participants with mild cognitive impairment but testing negative for Alzheimer’s indicators, and the healthy volunteers. And results from the virtual reality, or VR, exercise better discriminated between high- and low-risk individuals for Alzheimer’s disease than results on paper-and-pencil cognitive tests.

“These results suggest a VR test of navigation may be better at identifying early Alzheimer’s disease than tests we use at present in clinic and in research studies,” says Chan in a university statement. “We’ve wanted to do this for years” he adds, “but it’s only now that VR technology has evolved to the point that we can readily undertake this research in patients.”

The university says Chan is collaborating with colleagues at Cambridge to develop mobile apps to help diagnose early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. “We live in a world where mobile devices are almost ubiquitous,” notes Chan, “so app-based approaches have the potential to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease at minimal extra cost and at a scale way beyond that of brain scanning and other current diagnostic approaches.”

More from Science & Enterprise:

- Virtual Reality Harnessed to View Inside Blood Vessels

- Virtual Reality Coupled with EEG for Autism

- Virtual Reality Illness Fix in Development

- Virtual Reality Therapy Company Gains $5.1M in Early Funds

- Virtual Reality Harnessed for Stroke Rehab

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.