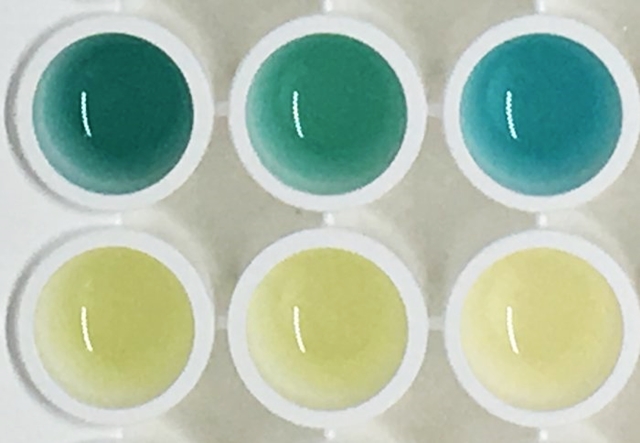

Urine samples from mice at top turned blue detecting colon cancer, while urine from healthy mice did not change color. (Imperial College London)

4 Sept. 2019. Biomedical engineers and materials scientists developed a simple urine test that in samples from lab mice show they can screen for colon cancer. Researchers at Imperial College London and Massachusetts Institute of Technology describe the tests and their findings in the 2 September issue of the journal Nature Nanotechnology (paid subscription required).

A team from the labs of biomaterials scientist Molly Stevens at Imperial College and MIT engineering professor Sangeeta Bhatia are seeking faster and easier methods for detecting disease at the point of care. Many routine screening tests, even if non-invasive, require analysis in remote laboratories by trained staff. In this project, Stevens, Bhatia, and colleagues are aiming for tests that can be conducted in the field and even at home without special equipment or training.

The researchers designed their screening technology to test for protease enzymes in urine as indicators of disease. Proteases break down large protein molecules into shorter peptide chains or amino acids. Various proteases result from chemical reactions in the body, and the presence of these enzymes in blood or urine act as indicators of specific diseases.

For this proof-of-concept study, the team looked for a particular type of enzyme called matrix metalloproteinases, an indicator of tumor cells. Metalloproteinases break down the extracellular matrix in cells, and their heightened presence indicates a high likelihood of a tumor growing or spreading to other parts of the body. In this case, the team looked for a specific metalloproteinase known as MMP9, an indicator of colon cancer and other diseases.

To detect the presence of matrix metalloproteinases, the researchers devised extremely small clusters of gold particles, no larger than 2 nanometers wide — where 1 nanometer equals 1 billionth of a meter — so they’re not filtered out by the kidneys. The gold in the clusters also turns blue in urine. The team coated and bound the nano-clusters with proteins that degrade in the presence of MMP9 enzymes.

If there’s no presence of MMP9 enzymes, the clusters are too large to pass through the kidney filters, and will not be present in urine. If, however, MMP9s are in the blood, they will break down the protein coat, and allow the uncoated gold nano-clusters to enter the kidneys, and thus be expelled through blue-colored urine.

The researchers tested their screening technology by injecting the nano-clusters into the blood of 14 lab mice induced with colon cancer, compared to 14 healthy mice. In less than an hour, urine from mice with colon cancer shows a deep blue color, while urine from healthy mice shows no change in color. In addition, the mice show no evidence of retaining the nano-clusters, nor any signs of toxicity after four weeks.

The researchers say the gold nano-clusters can be adapted to test for specific diseases, beyond cancer. But the technology still needs further refinement and testing before its ready for human clinical trials. Nonetheless, the researchers believe the gold nano-clusters offer a promising platform to develop fast, inexpensive, easy-to-use screening tests for a range of diseases.

“By taking advantage of this chemical reaction that produces a color change,” says Stevens in an Imperial College statement, “this test can be administered without the need for expensive and hard-to-use lab instruments. The simple readout could potentially be captured by a smartphone picture and transmitted to remote caregivers to connect patients to treatment.”

Stevens, Bhatia, and the two lead authors Colleen Loynachan and Ava Soleimany, are listed as inventors on a U.S. patent application for the technology. And Bhatia is a co-founder of Glympse Bio, a company in Cambridge, Massachusetts developing simple screening and diagnostics for disease with biological sensors and urine tests.

More from Science & Enterprise:

- Nanotube Fibers Configured for Heart Repair

- Nanotech Vaccine Aids Melanoma Immunotherapy

- Artificial DNA Designed to Control Drug Delivery

- Gold Nanoparticles Boost Crispr Delivery

- DNA Nanoscale Capsules Designed for Drug Delivery

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.