8 Nov. 2019. A miniaturized bio-electronic device implanted in a pig can process filtered blood like a real kidney without triggering an immune response or blood clots. Developers of the device from University of California in San Francisco and partner institutions reported on the advance yesterday at the Kidney Week meeting in Washington, D.C., sponsored by American Society of Nephrology.

The tested device is a bio-reactor, part of an implanted artificial kidney in development by the Kidney Project, an initiative of UC San Francisco and Vanderbilt University in Nashville. The artificial kidney aims to help people with end-stage renal disease, a life-threatening condition where the kidneys almost completely fail, and the only treatment options are frequent dialysis sessions to clean impurities from the blood, or a transplanted kidney with donors in short supply. According to the Kidney Project, some 750,000 people in the U.S. and 2 million people worldwide have end-stage renal disease.

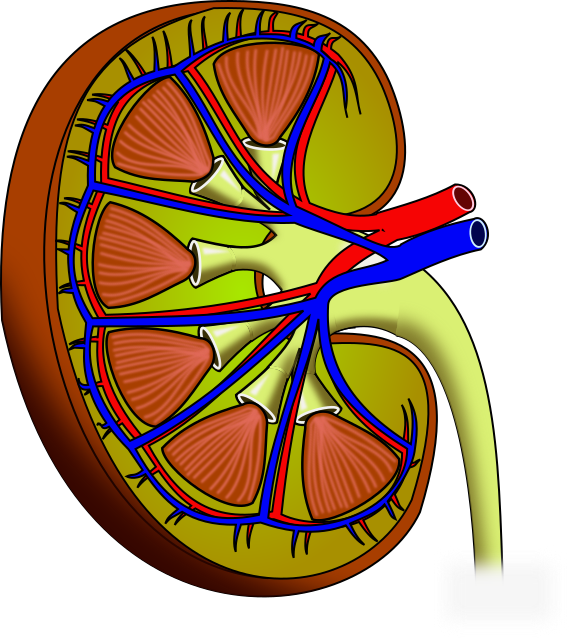

The Kidney Project’s device has a filter to capture impurities in blood and a bio-reactor to perform metabolic functions. The filter has silicon membranes with pores less than 10 nanometers in size, where 1 nanometer equals 1 billionth of a meter. The bio-reactor has tubule cells from human kidneys that process the filtered blood plasma into urine, maintain healthy pH and potassium levels in the blood, as well as produce essential hormones. The silicon filtering membranes also seal off the tubule cells in the bio-reactor to prevent an immune-system reaction.

The researchers first bench-tested the artificial kidney to evaluate the system’s performance in simulated conditions. The simulated lab tests show the bio-reactor enables filtered plasma to flow through, with more than 90 percent of the human tubule cells remaining viable. When implanted into a pig for three days, an animal with organs about the same size and functionality of humans, more than 90 percent of the tubule cells also remain viable, and with no blood clotting. In addition, the device does not cause an immune reaction in the pig, which suggests it may not need drugs to suppress these reactions in humans.

Shuvo Roy, a bio-engineering professor at UC San Francisco and technical director of the Kidney Project says in a university statement released through EurekAlert, “We couldn’t use the standard blood-friendly coatings that have been developed for heart valves, catheters, and other devices because they are so thick that they would completely block the pores of our silicon membranes. One of our accomplishments has been to engineer a suitable surface chemistry on our silicon membranes that makes them look biologically friendly to blood.”

The project’s goal is a device that can be powered by electrical signals from the heart, while still remaining small and friendly to the immune system, without the need for extra drugs. The team now plans to scale up the bio-reactor to include more tubule cells and test the device in animals with induced kidney failure, with the eventual goal of human clinical trials.

Roy and Kidney Project medical director William Fissell at Vanderbilt University are founders of the company Silicon Kidney LLC in San Francisco, commercializing the project’s technology. Silicon Kidney is the recipient of several Small Business Innovation Research grants, the latest in 2018 from National Institutes of Health for an implantable dialysis system to treat people with end-stage renal disease.

More from Science & Enterprise:

- Engineered Organ Transplant Company Raises New Funds

- Artificial Pancreas Improves Blood Glucose Control

- Implanted Overdose Rescue Device Being Developed

- Leg Prosthetic System Restores Sensory Feedback

- Trial Underway Testing Brain-Computer Implant

* * *

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

You must be logged in to post a comment.